After ratcheting up interest rates over the last two years, the US Federal Reserve used its 13 December meeting to open the door to rate cuts next year – a move its peers will ultimately follow, but not just yet.

Nadia Gharbi, Senior economist, Xiao Cui, Senior Economist Pictet Wealth Management.

A change in the Federal Reserve’s tone and projections mark a major policy pivot away from its tightening cycle, bringing interest rate cuts into view as the US central bank aims to achieve a “soft landing” for the world’s largest economy next year.

The Fed’s shift in stance at its 13 December policy meeting set it apart from other major central banks that met a day later and were more cautious – for now. Distinguishing it from other leading banks, the Fed has a dual mandate – to achieve maximum employment, as well as stable prices. The European Central Bank and others have a tighter focus on inflation.

ECB President Christine Lagarde said the bank’s policymakers “did not discuss rate cuts at all” and that they still had work to do to tame price pressures. The Bank of England also left its main interest rate unchanged and said monetary policy is “likely to need to be restrictive for an extended period of time.” The SNB left rates on hold as well, confirming it had finished with hikes without indicating that a cut could come soon.

By contrast, new forecasts issued at the Federal Reserve meeting showed the median Fed official now expects 75 bps in cuts next year compared to 50 bps in the previous “dot plot” projections in September. Chair Jay Powell said the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) also discussed when it would be right to cut rates.

“The question of when will it become appropriate to begin dialling back the amount of policy restraint in place – that begins to come into view, and is clearly a topic of discussion out in the world and also a discussion for us at our meeting today,” he said.

Powell’s comments marked a remarkable change in position. Just two weeks earlier, he said it would be “premature” to conclude with confidence that the Fed had achieved “a sufficiently restrictive stance, or to speculate on when policy might ease”.

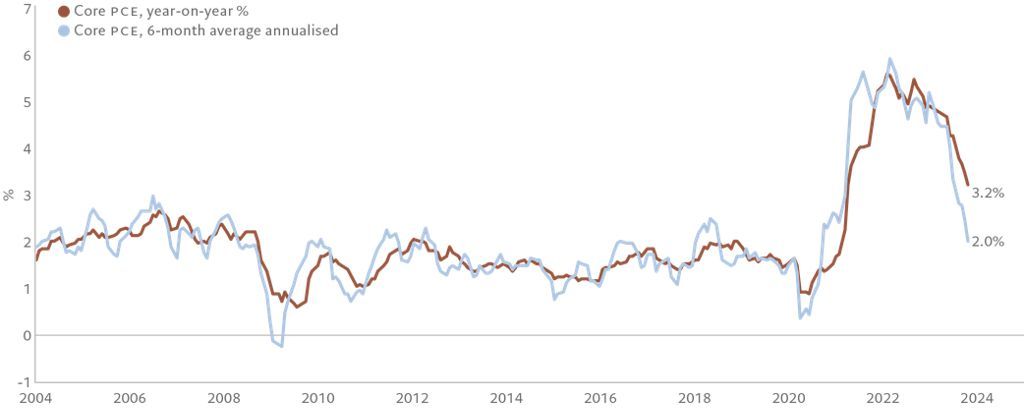

The shift in tone was driven by data showing the Fed’s clear progress in easing price pressures. Recent CPI and PPI data have reinforced a disinflationary picture, as shown in the Fed’s favoured inflation measure, the core personal consumption expenditures index (PCE).

US inflation eases

Having been slow to jump on inflation in 2021, when it described rising prices as “transitory”, the Fed appears eager to be sharper in reacting to the economic slowdown to achieve a soft landing. Policymakers were focused on not keeping rates too high for too long, Powell said.

The Fed’s “restrictive stance of monetary policy is putting downward pressure on economic activity and inflation,” he added. Beginning in March 2022, the Fed raised rates 11 consecutive times, taking its benchmark rate to a 22-year high.

Now, the Fed’s policy pivot raises the risk that it cuts rates as soon as March, rather than in June, as we have forecast.

“The Fed’s policy pivot raises the risk that it cuts rates as soon as March.”

However, it is worth noting that there was a wide dispersion in the latest “dot plot” forecasts from Fed officials and the coming days may see some pushback to Powell’s message from other Fed speakers.

In Europe, Lagarde tried to buy some time for the ECB but, with inflation slowing markedly, a pivot is coming in the euro area pretty soon too. We expect the ECB to make its first rate cut in mid-2024 but there is a risk it cuts earlier. In Switzerland, the SNB revised down its inflation forecast, in particular for 2025, and is effectively performing a subtle pivot.

With central banks edging their way towards rate cuts, we remain of the view that now is a good time to switch from cash into fixed-income instruments to lock in attractive yields while they are still on offer.