The volatility of the fixed income market has left

investors wary. But the yields offered by shorter-

dated bonds are as attractive as they have been in

quite a while.

Mickael Benhaim, Head of Fixed Income Investment Strategy & Solutions Pictet Asset Management.

With bonds whipsawing on the way to taking some of their biggest losses in decades, investors can be forgiven for feeling gun-shy about the fixed income market. But in doing so, they also run the risk of missing out on some of the most attractive risk-adjusted returns around. Because short-dated bonds offer just that right now.

At the heart of the fixed income market’s recent woes is uncertainty about what policy course the world’s major central banks, particularly the US Federal Reserve, are likely to take over the coming months. Policymakers face a dilemma between avoiding a recession and getting inflation back to target.

The uncertainty is being factored into the long end of the yield curve – bonds with the longest maturities. The yield on the US 10-year Treasury bond, which was hovering around 3.5 per cent at the start of the year, has recently breached 5 per cent.

Conditions are markedly less problematic at the shorter end of the bond curve. Here, investors can find some of the highest yields in more than a decade – enough to keep them from suffering a decline in total returns even if monetary policy tightens further. Yields on bonds with maturities of between one and three years compare favourably with what’s available across what has been a persistently flat yield curve, including money markets. But unlike long dated bonds, they offer a degree of protection against additional rate hikes (see Figs. 3 and 4) should inflation fail to drop.

Second guessing central banks

Until roughly the start of this year, bond markets were convinced that the dramatic run of rate hikes central banks had delivered during the course of 2022 would not only drive inflation back to target but would also trigger recession. As a consequence, bonds were pricing in expectations of a short-lasting peak in rates, followed by steep cuts, particularly in the US.

But with inflation proving stickier than anticipated and economies more robust, those certainties have evaporated. For instance, the market no longer thinks the Fed has tightened policy enough to return inflation back to its 2 per cent target over a reasonable time horizon.

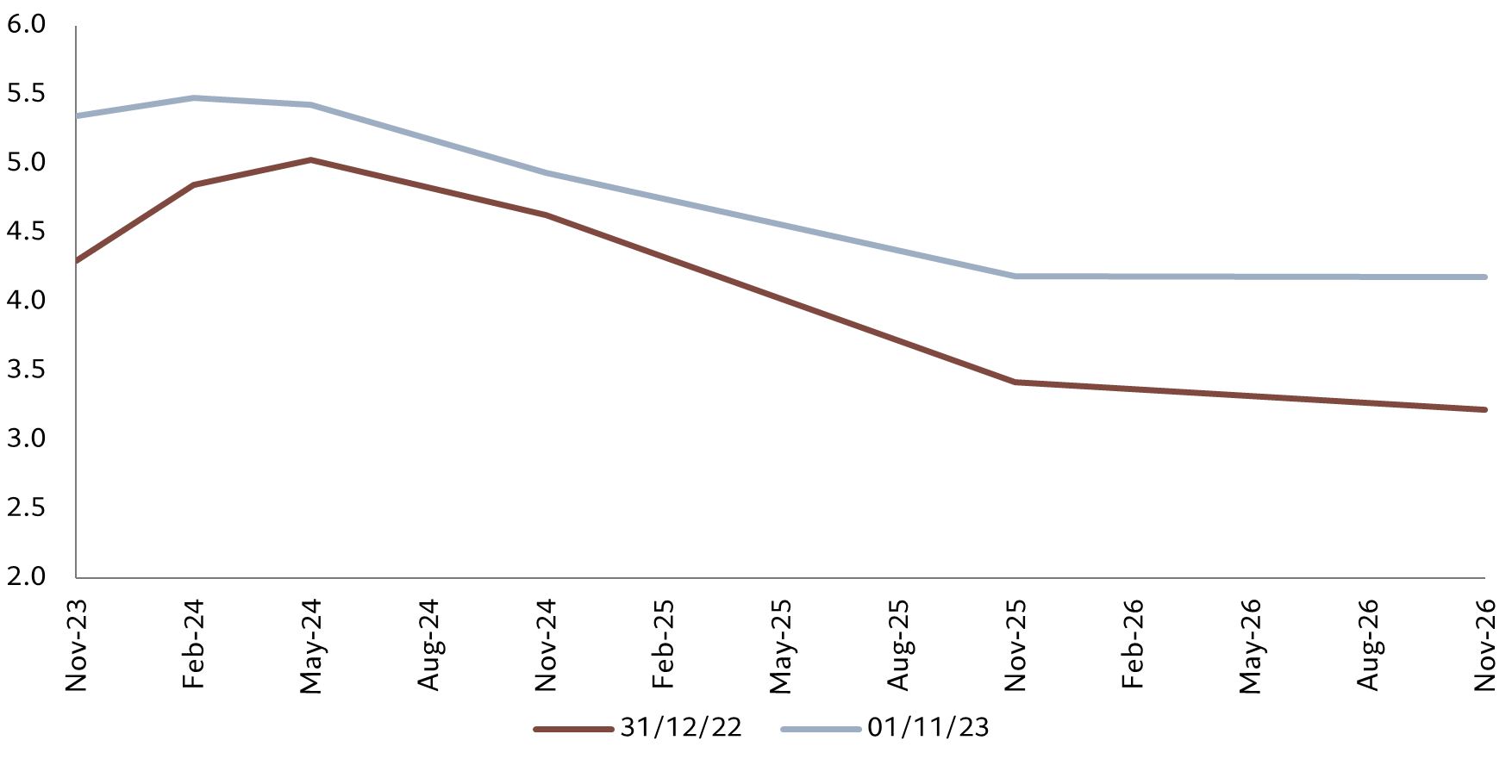

Fig. 1 – Whiplash

Implicit path of future Fed funds rate at 31.12.2022 and 01.11.2023, %

Sticky inflation, in turn, means that the Fed won’t be cutting rates nearly as soon or as quickly as markets had been hoping. Expectations are now that the Fed funds rate will stay at current levels of 5.25 between 5.5 per cent – if not higher – for a significant period. This has prompted a significant selloff at the longer end of the bond market (see Fig. 1).

But even when rates do start coming down, they won’t drop back to where they were in the decade following the global financial crisis. To see why, it’s worth looking at what makes up bond yields.

Finding the neutral

Economic theory dictates that the real neutral interest rate is where demand for savings and investment balances. During the past decade that neutral rate was close to zero, thanks in part to a high demand for savings in Asian economies, increasing numbers of people building up retirement funds and subdued demand for investment.

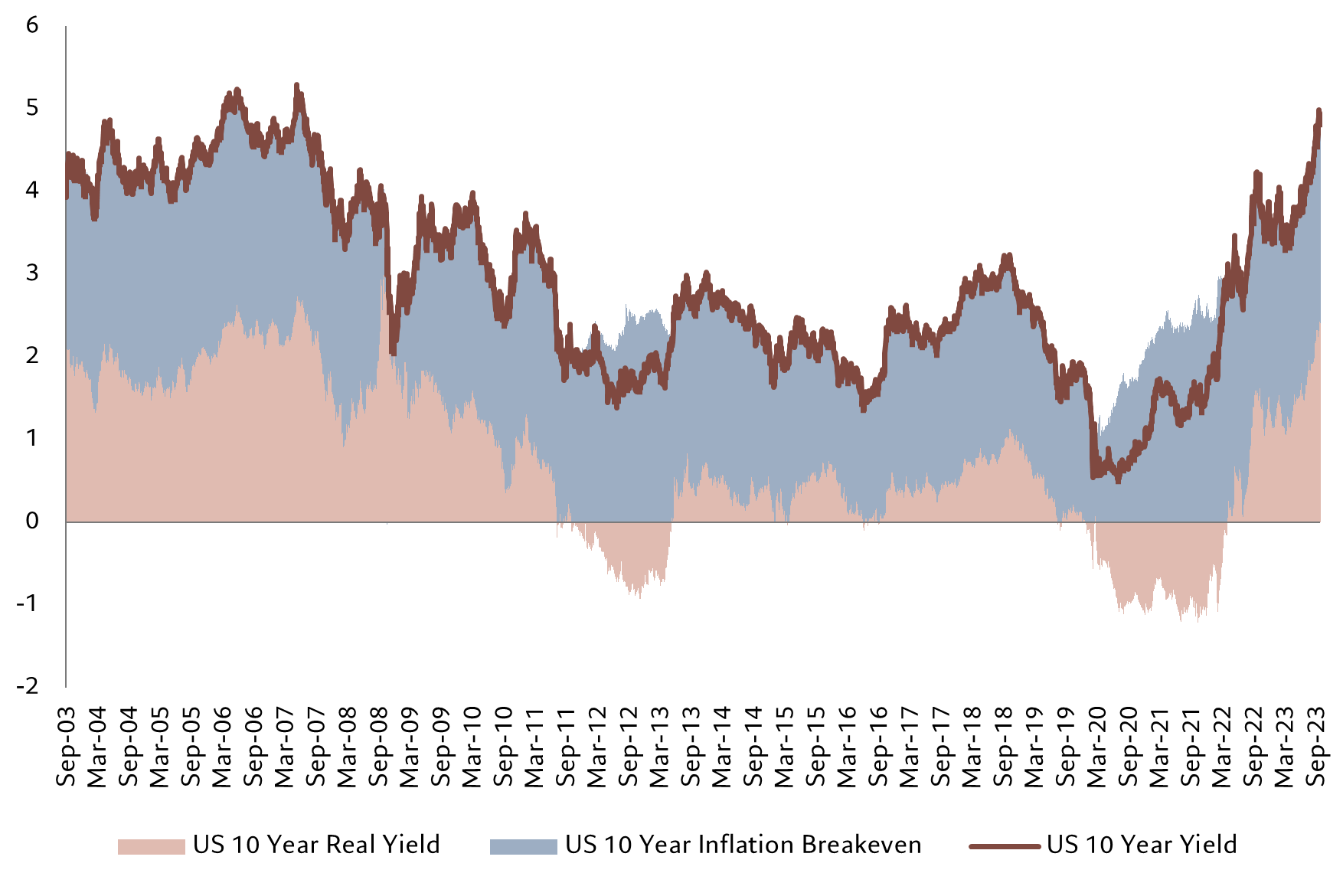

But those dynamics are now changing in ways that could keep rates at higher levels than investors have been used to. For one thing, there is likely to be huge demand for investment, not least related to the energy transition and the development of artificial intelligence. With savings not expected to grow at the same pace, there is a bound to be an upward shift in the neutral rate of interest from its trough of the past decade (see Fig. 2).

For the US, estimates range from 0.5 per cent to around 2.5 per cent for the neutral rate – we tilt towards the latter. Once inflation expectations and the term premium are factored in, this suggests a minimum nominal yield on longer dated Treasury bonds of around 4.5 per cent – 2 per cent for target inflation, 2 per cent for the neutral rate plus a slight positive term premium.

Fig. 2 – Breaking it down

Composition of US 10 year Treasury bond yields, broken down into real rate and inflation breakeven, %

Higher rates, but only just restrictive

All of this suggests that the Fed’s series of rate hikes has only just reached the point at which monetary policy is restrictive. And even then, there are factors limiting how much traction those rates are having in the real economy. For one thing, US households tend to have 30-year mortgages and many outstanding loans are at significantly lower interest rates; furthermore a substantial tranche own their houses outright. And although households have eaten into the excess savings they built up during the Covid pandemic, around a third of the money remains untouched, buffering them from a change in the economic weather. Meanwhile, corporations which borrowed money at ultra-low rates during the pandemic won’t start rolling that over in any significant volumes until later next year.

“The era of zero or negative bond yields is over”

Finally, the US government is running massive deficits – essentially fiscal stimulus is offsetting monetary braking. The additional complication here is uncertainty about how these deficits are to be financed. Will the government issue long-dated bonds at a time when the Fed is undergoing a quantitative tightening policy, threatening to give the market a historic bout of indigestion?

Together these factors are likely to keep investors in a state of heightened uncertainty. Eliminating some of this uncertainty – say with further Fed tightening – could well drive down long dated yields, even as it forces the curve up at the short end. But that’s not a central scenario.

Where that leaves investors…

Bond investors are right to be uneasy about the long end of the curve. They’ve taken some hefty losses on what they’d thought was a safe asset class during the past two years. However, they are being paid enough in real yields – 10-year US Treasury inflation-indexed bonds are delivering 2.5 per cent. Historically this is a strong real return for what are safe assets.

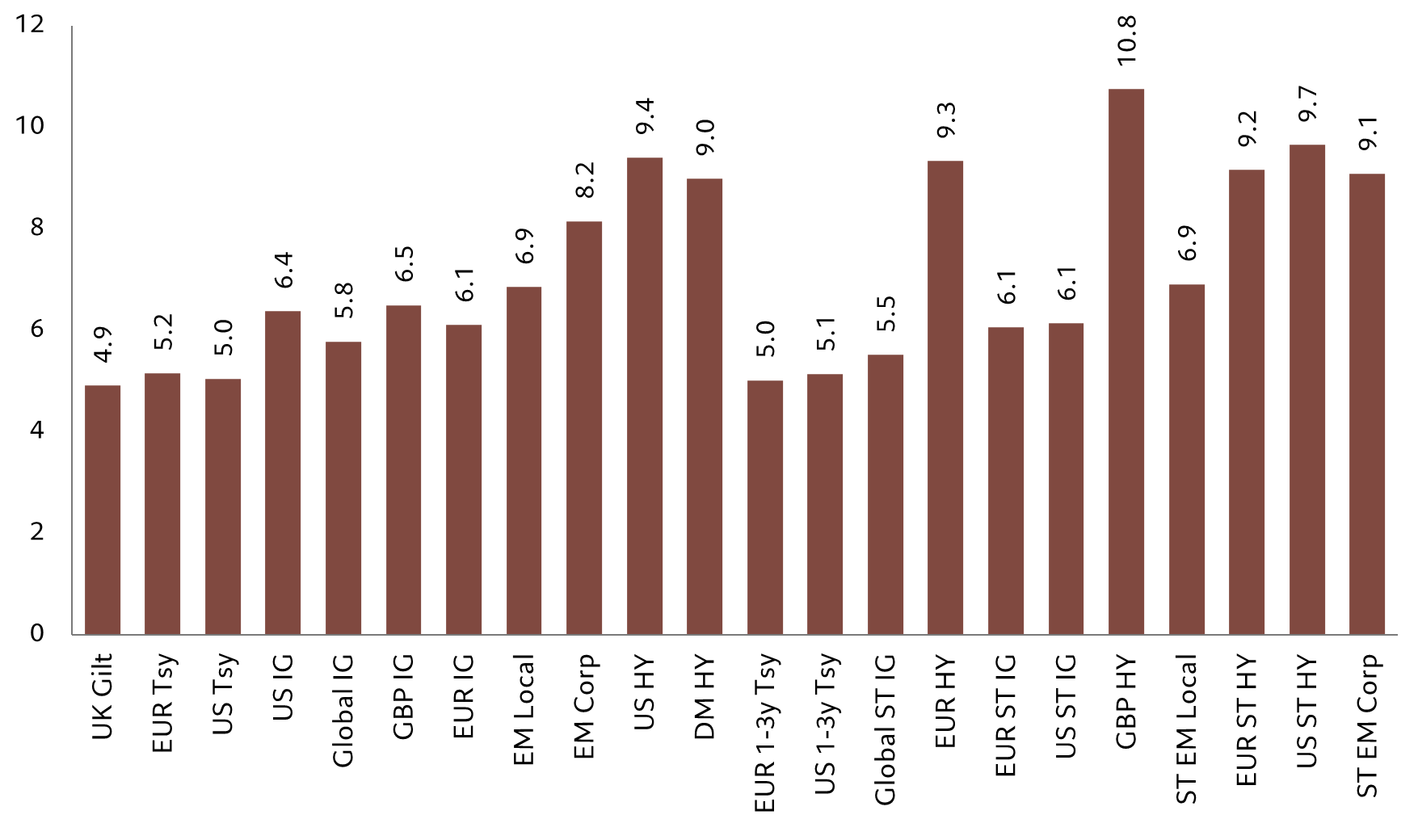

More eye-catching are the returns on offer at the short-end of the bond curve. Investors are being rewarded with significant yields across many bonds and credit instruments. Indeed, our research shows that the coupons on these instruments are substantial enough that the bonds would produce positive returns even with substantial further rises in official rates.

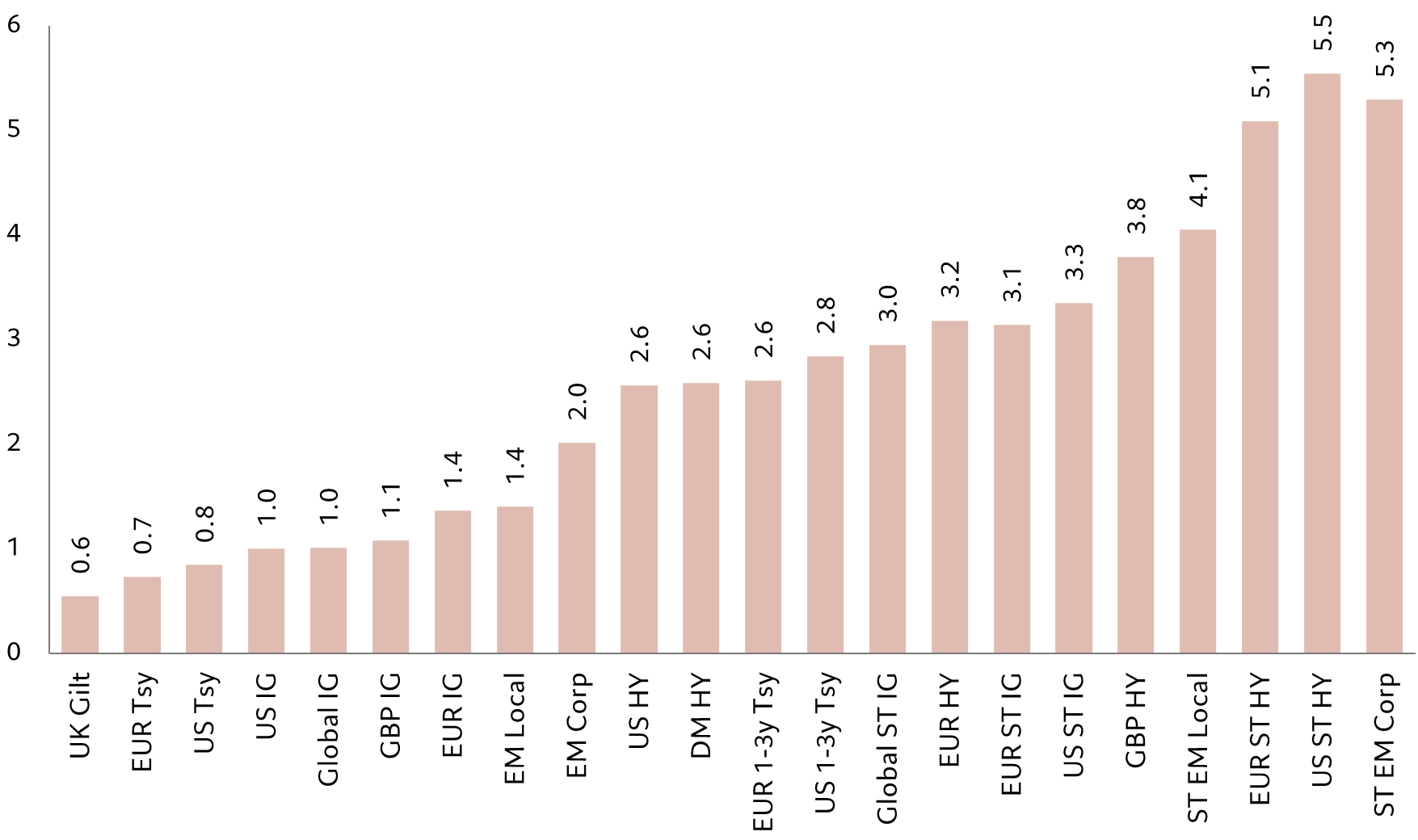

Our analysis shows that short-dated bonds are a sweet spot in the fixed income market. They offer an uplift in yields on money market funds, but without the risks longer duration bonds face. So, US short-term high yield credit offers a yield of 9.7 per cent (in US dollars) against money market yields of some 5.3 per cent. The breakeven of 5.5 per cent means that these bonds can also withstand a doubling of official US interest rates in a year before suffering a loss. While longer dated US high yield credit is also offering a substantial yield to maturity – 9.4 per cent – its breakeven is only half that of the bonds maturing in 1 to 3 years (see Figs. 3 and 4). It’s a similar story across the universe of short-dated bonds.

Fig. 3 – Hefty yields

Yield to maturity for different fixed income classes, USD terms, %

ST refers to short-dated instruments with 1-3 year maturities.

Fig. 4 – Margin of safety

Breakeven* rates on various bonds, %

*Breakeven is the amount official interest rates could rise before investors would face taking capital losses over one year.

As the economic cycle progresses and growth slows, official interest rates will undoubtedly come down with inflation. But investors expecting a return to the world in the decade or so after the 2008 crash are likely to be disappointed. Rates will be higher than they were then. The era of zero or negative bond yields is likely over – inflation is likely to stay higher than we’ve been used to, while long-run structural factors suggest that investors will benefit from positive real rates. Uncertainty over central bank policy and sticky inflation points to an era of heightened volatility, which tends to have the biggest effect on long dated bonds. By contrast, investors in short-dated bonds benefit from the prevalent high yields, while also knowing that official rates can climb much further before they suffer any loss to their capital.