By Prof. Rd. Jan Viebig, Chief Investment Officer, ODDO BHF SE

Those who expected that Donald Trump’s first policy move would be to cut taxes were wrong. On 1 February, the White House opened fire with trade policy, introducing a first raft of measures raising import tariffs on goods from Canada, Mexico and China, to 25% for its immediate neighbours to the north and south (but 10% on Canadian energy raw materials), and by an extra 10% on goods from China. Until recently, Chinese exports attracted average tariffs of just over 19%. The proposed measures are based on the International Emergency Economic Powers Act and are justified as necessary to compensate for the lack of action on the part of foreign countries to prevent illegal immigration and the flow of drugs into the US.

Markets reacted immediately, largely with scepticism. Following the tariffs announcement, the US equity market, already shaken by the release of DeepSeek, temporarily lost almost 2%. It stabilised after Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum announced that she had agreed in a call with Trump to a 30-day moratorium. Sheinbaum promised to take measures to secure the border against drug smuggling and illegal immigration by dispatching additional security forces to the area. A few hours later, Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau reported similar success after a speaking on the phone with Trump. Beijing, clearly prepared for this eventuality, announced retaliatory measures, including tariffs on a range of energy products, agricultural machinery, pick-up trucks, and large-displacement vehicles, as well as export restrictions on some minerals and an anti-monopoly investigation against Google. Overall, experts see the Chinese reaction as a shot across the bow. The door is likely to remain open for trade talks. Conversely, Trump has also announced his willingness to speak by phone with Xi Jinping, although an initial appointment fell through.

Mexico and Canada would suffer serious consequences if the new tariffs are introduced. The Brookings Institution estimates that they would lead to a fall in real gross domestic product (GDP) of more than 1% for both countries, if they refrain from taking countermeasures. The dampening effect on American GDP, on the other hand, would be much smaller at -0.2%. Tariffs would have a more significant impact on prices in the US, driving them up by around 1.3%, while the impact on Canada and Mexico would be deflationary. If Canada and Mexico took similar countermeasures, the negative impact on Canadian and Mexican GDP would be markedly larger (-3%), but the price effects would be reversed. In the US, GDP losses would be somewhat higher (-0.3%), but the price effect would be weaker (+0.8%).

By announcing import tariffs of 25%, the US government has pulled out a big trade policy stick, only to then settle for a few concessions to secure the borders against drug trafficking and illegal immigration, at least for the time being. This can be seen as a sign that the US is not blindly tightening the tariff screw but rather proceeding in a manner that takes into account the economic risks of these measures. Trump may also be using the domestic stock market reaction as an indicator of the political direction he should take. The president’s principal trade policy advisor, Peter Navarro, spoke this week of a “measured approach”.

Nevertheless, it would be unwise to assume that Trump is just bluffing. In the case of Canada and Mexico, political goals are the primary focus, namely drugs and immigration. But the president’s executive order of 20 January on foreign trade leaves little doubt that US trade policy also pursues other, primarily economic goals. The top priorities are combating unfair trade practices, reducing the country’s trade surplus, and generating revenue. To manage this new revenue stream, a new agency called the External Revenue Service will be created, contrary to the prevailing trend. In his inaugural speech, Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent said: “Instead of taxing our citizens to enrich other countries, we will tariff and tax foreign countries to enrich our citizens.” The President’s executive order sets a deadline of 1 April to finalise these tariff measures.

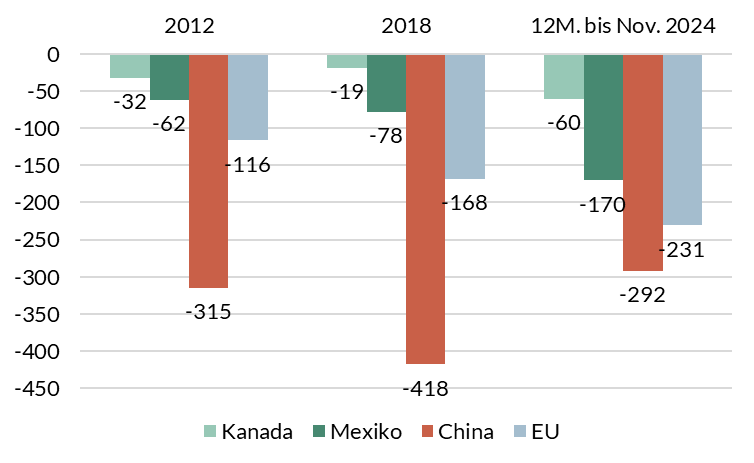

For Europe, things are likely to get serious. This is about more than obtaining a few political concessions, such as increased defence spending or more equitable sharing of the cost of the war in Ukraine. The European Union (EU) sent more than USD 600 billion worth of goods to the US in the 12 months to November 2024, representing almost 20% of all US imports (vs. 13% from China). European countries thus contributed USD 231 billion to the US trade deficit of USD 1,182 billion (vs. USD 292 billion for China). In addition, the US trade deficit with China has fallen significantly since 2018, by around USD 126 billion, no doubt due mainly to the tightening of US trade policy. The trade deficit with the EU increased by more than USD 60 billion over the same period.

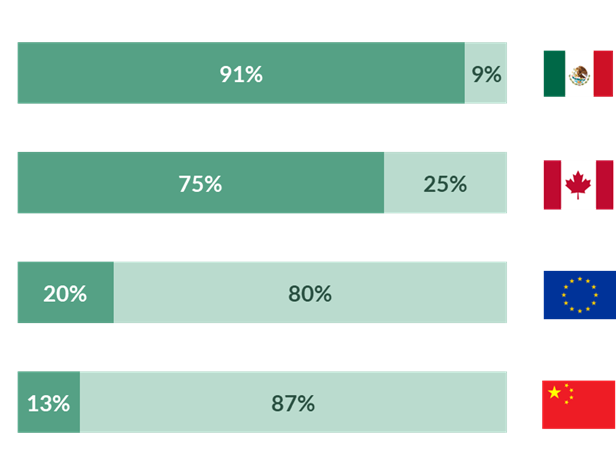

Fig. 1: US share of total goods exported by selected countries (2023)

Source: Eurostat, U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, Factset

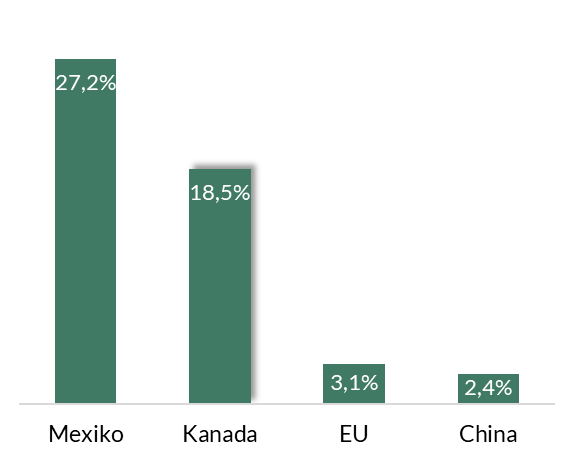

Fig. 2: US trade as a share of GDP, selected countries, 2024.

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis, IMF; *) 12-month cumulative imports of goods by country, Dec. 2023 to Nov. 2024, relative to nominal gross domestic product in 2024 (IMF estimate)

However, trade policy does not give the US the same leverage over EU states as it does over Canada and Mexico, for whom the US is the principal trading partner, accounting for just under 19% of GDP for Canada and 27% for Mexico. Meanwhile, Canadian and Mexican imports account for just over 3% of GDP for the much larger US economy. Europe is in a more favourable situation: exports to the US account for just over 3% of EU GDP (China: 2.4%). The overall economic risks posed by US tariffs are therefore much lower for Europe.

Nevertheless, it would be foolish to underestimate their impact. First, because the effect is by no means negligible: Goldman Sachs estimates the potential loss of economic output due to higher US tariffs at 10%, which works out to a 1% decline in real GDP (assuming the EU takes comparable countermeasures). Given Europe’s already weak growth this presents a serious challenge. Second, competitive pressure will increase if US tariffs also affect third countries. Lower sales to the US are already causing manufacturers to redirect goods to other countries. China has thus increased its exports to the EU in recent years. Third, US trade policy appears to be targeting the European auto industry. The Oxford Economics Research Institute has concluded that a 25% tariff on European automobiles exported to the US would lead to a fall of 7% in German and Italian automobile exports; value added for this important industrial sector could fall by around 5% in both countries. Spain and France would be less exposed due to lower exports to the US, with a decline in auto exports of around 2% and a fall in value added of slightly less than that. US tariffs could have a very different impact depending on the region, but Germany would probably be more exposed than the European average.

Fig. 3: Trade balance in goods with the US, largest US trading partners (in billion USD)

Source: U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis

The trade ambitions of the Trump administration are driving up overall risks for the global economy. The president is clearly prepared to threaten global growth in exchange for uncertain advantages for the US. Europe and Germany must get ready to face the next salvo of trade measures. How should governments prepare for this eventuality? On the one hand, US demands must be taken seriously, and efforts made to determine to what extent they can be accommodated. Increased defence spending by NATO members in Europe, for example, is not an unreasonable demand. On the other hand, the EU needs to agree to a clear and united plan for trade countermeasures. The next German government should contribute in a constructive and competent manner to this process. This is particularly important for the German automotive industry, which is likely to be a central point of contention in the trade dispute with the US. Above all, we must work to strengthen our own competitiveness and growth potential. If the US government applies economic common sense and proportionality in its policies, European economies should be able to weather the storm.