Prof. Dr. Jan Viebig, Chief Investment Officer ODDO BHF Asset Management.

US President Donald Trump’s economic policy poses significant risks to financial markets and currency relations. Curbing the US trade deficit is undoubtedly high on Trump’s agenda, but this priority could also have serious repercussions on the global exchange rate structure. So far, tariffs have been the central element of Trump’s trade policy. Since “Tariff Man” took office, hardly a day goes by without headlines announcing new, suspended, or threatened tariffs. A tariff package comprised mainly of so-called “reciprocal tariffs” will come into effect on 2 April, renamed “Liberation Day” by Trump.

In addition to tariffs, the current administration may also be pursuing a second approach to reduce the US trade deficit: devaluing the US dollar. The so-called “Mar a Lago Accord” is the brainchild of economists Stephen Miran and Zoltan Poszar. Miran, a former strategist at an investment firm, was recently appointed chairman of the Council of Economic Advisors. He argues that the US dollar is systematically overvalued due to its use as a reserve currency and international means of payment. The inelasticity of demand (i.e., insensitivity to price or quantity signals) of foreign currency reserves prevents the dollar exchange rate from balancing the US trade balance.[i]

Miran’s Mar-a-Lago Accord proposes a strategy for devaluing the dollar. The name of his proposal references a series of monetary policy agreements reached by major industrialised nations in the 1980s. The Plaza Accord (named after the Plaza Hotel in New York where the meeting took place in September 1985) stated that “some further orderly appreciation of non-dollar currencies is desirable” and that monetary authorities of the relevant nations would “stand ready to cooperate more closely to encourage this.” Roughly two years later, the Louvre Accord agreed to counteract further devaluation of the dollar through more expansionary economic policies in non-dollar countries. The decision to name the Mar-a Lago-Accord after Trump’s Florida residence is presumably calculated to win the president’s support.

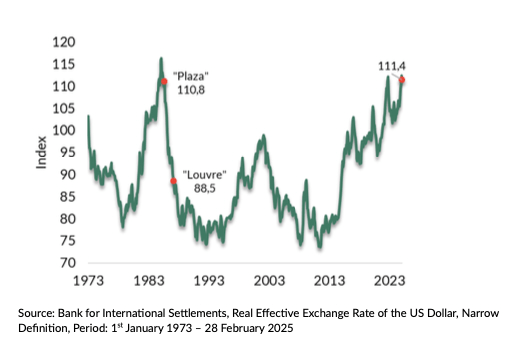

There are several parallels between the economic situation in mid-1985 and today. Then as now, an expansive fiscal policy combined with strong growth and restrictive monetary policy contributed to a rapid rise in the US trade deficit, budget deficit, and capital inflows from abroad, driving up the dollar. However, by September 1985, the dollar had already weakened significantly from its peak in February 1985. Over this period the USD/DEM (Deutschmark) rate fell from DEM 3.45 to DEM 2.85, an 18% decline.[ii] Between the Plaza in September 1985 and the Louvre in February 1987, the dollar depreciated by a further 36% to nearly DEM 1.80. Figure 1 illustrates the evolution of the trade-weighted exchange rate of the dollar against the currencies of major trading partners, adjusted for inflation, and clearly shows that its value is currently approaching that of the Plaza Accord period.

Figure 1: Real trade-weighted effective exchange rate of the USD vs the currencies of major global trading partners

While in 1985, US Treasury Secretary James Baker sought a cooperative solution to the overvaluation of the USD, Miran’s proposal offers only threats and intimidation, in line with Donald Trump’s bully-boy tactics. The aim is not only to initiate a devaluation of the dollar but simultaneously (or primarily) also to make a “deal” that benefits mainly the US. This would be achieved by persuading foreign monetary authorities that use the dollar as a reserve currency to exchange their dollar holdings (mainly T-bills) for non-tradable, 100-year bonds with no coupon payments. If a central bank needs liquidity, these bonds could be used as collateral for short-term loans. To gain their cooperation, the US would use the threat of tariffs and a withdrawal of US security guarantees as leverage.

According to US Treasury Department data, as of January 2025, USD 28.5 trillion worth of US government bonds are in circulation, of which USD 8.5 trillion (30%) are held by foreign creditors, including USD 3.8 trillion (13%) by central banks. That’s hardly small change. The largest “official” creditors include China, Japan, and European nations.

In fact, converting T-bills to 100-year bonds would amount to expropriation – or even default. Assuming an interest rate of 4%, for example, USD 1,000 at current market value would be worth less than USD 20 a hundred years from now. In addition, the converted bonds would be useless to foreign central banks as a monetary policy tool since they would not be tradable. Borrowing against them would help alleviate this problem somewhat, at the risk of subjecting nations to the whims of US policy and creating new forms of dependence. Lastly, creditors would earn no interest income from these bonds. In other words, the benefits of the Mar-a-Lago Accord are decidedly one-sided and offer few reasons for foreign nations to agree to its terms.

From an economic perspective, an aggressive tariff policy and a devaluation of the dollar are fundamentally incompatible objectives. Both past experience and economic theory indicate that import tariffs tend to drive up a country’s currency. The purported aim of the Mar-a-Lago Accord, however, is to devalue the dollar. This incoherence is bound to create uncertainty and volatility in currency markets.

Furthermore, Miran is overly fixated on foreign exchange reserves as a cause of the dollar’s overvaluation. There is no doubt that the USD is significantly overvalued, based on criteria such as purchasing power parity and the trade balance. However, it seems unlikely that this has been caused by growth in USD reserves in countries with trade surpluses with the US. Even China has increased its foreign exchange reserves only gradually since the mid-2010s. A more likely culprit is the massive inflow of international investment capital into the US in recent years, incentivised by high interest rates and the superior growth potential of US companies.

We believe that coercing the US’s creditors to accept such punitive terms would have the effect of a bomb on the global financial system and the dollar’s position as an international trade currency, potentially triggering a flight from US government debt and the dollar. The mere discussion of these measures heightens uncertainty and volatility. An international reserve and investment currency such as the dollar depends on investors’ confidence in the stability of their investments, which is underpinned by legal certainty and creditworthiness. If this confidence is shaken, the dollar will suffer, and US bonds and stocks will see their yields and risk premiums increase significantly. In its current form, the Mar-a-Lago Accord is poison for financial markets. It is in everyone’s interest that Donald Trump refrain from engaging in such a dangerous game.

[i] “The root of the economic imbalances lies in persistent dollar overvaluation that prevents the balancing of international trade, and this overvaluation is driven by inelastic demand for reserve assets.” Stephen Miran (2024), “A User’s Guide to Restructuring the Global Trading System”, Hudson Bay Capital, November 2024[ii] For reference: Using a fixed rate of EUR/DEM 1.95583, the DEM rate cited approximately EUR/USD 0.57.