Bruno Cavalier, Chief Economist ODDO BHF Asset Management.

KEY HIGHLIGHTS:

- For more than two years, monetary policy had been tightened almost everywhere in the world.

- Progress in disinflation from 2023 onward has enabled a reversal.

- Last year, policy rates were cut almost everywhere, except in Japan.

- At the outset of 2025, the Fed has shifted to pause mode, awaiting greater clarity regarding Trump’s maneuvers.

- In contrast, the ECB is prepared to continue lowering its rates to support the economy.

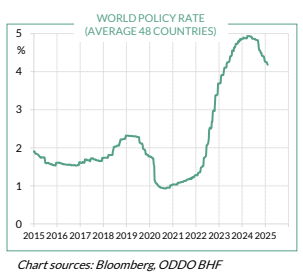

The reopening of the global economy following the 2020 lockdowns triggered a surge in inflation, prompting nearly all central banks to respond by raising their interest rates. Some emerging markets reacted as early as 2021—most notably in Latin America and Eastern Europe—while the United States and Western Europe followed suit in 2022. Two notable exceptions were China and Japan. Overall, the so-called “global” policy rate, calculated as a weighted average of the rates across countries, jumped by nearly 250 basis points in 2022 and by more than 125 bps in 2023 (chart).

As inflationary pressures truly eased, almost all central banks pivoted in the opposite direction. Last year, both the Fed and the ECB cut their key rates by 100 bps, while the global average decline was 60bps. However, in recent months the dynamics of inflation have diverged across regions. The United States, with its economy operating at full capacity, has seen inflation rebound. China teeters on the brink of deflation. Japan is emerging from two lost decades. Meanwhile, Europe struggles to ignite a genuine recovery in domestic demand, and inflationary pressures are moderating. In 2025, monetary policies are expected to be less synchronized than in recent years—and may even follow divergent paths. This divergence could have repercussions for other markets and currencies. Let us now review the main countries.

In the United States, last year defied predictions of a soft landing. Real GDP growth held close to 3% thanks to robust household demand—bolstered by an increase in net wealth of nearly 10% and strong job creation. Disinflation has stalled, and the attainment of the 2% target is no longer assured. Fiscal policy remains expansionary. Under these circumstances, the Fed has little reason to ease its policy in the near term.

Moreover, the Fed must take Donald Trump into account. Much like eight years ago—but this time with more ambitious goals—his agenda aims to fight illegal immigration, reduce taxes for households and businesses (despite an already very high budget deficit), and erect trade barriers. In an economy at full employment, all these measures are inherently inflationary. What remains unclear is the scale and sequencing of these initiatives.

Since embarking on his second term, the president has made multiple announcements of tariff increases. Some of these were almost immediately reversed (in the case of Colombia) or postponed (with Mexico and Canada) once the implicated countries pledged to tackle illegal immigration. Other increases in tariffs, particularly those affecting China, remain in place to date. Several additional hikes are looming for certain products (such as steel and aluminum) or regions (Europe).

The outcome of this confused communication is a surge in trade uncertainty nearly as pronounced in a few weeks as what was observed over two years during Trump’s first term. Pending further clarity, the Fed has opted to remain on hold—even if this draws criticism from the president, who would prefer to see interest rates lowered without delay.

In the eurozone, cyclical conditions are diametrically opposed to those in the United States. Economic growth is weak and below potential. In 2024, growth was driven by exports, but this engine may lose momentum in the event of a trade war. The only favorable development has been a recovery in bank lending flows. Otherwise, no indicators are showing green lights. Business sentiment is below normal amid political uncertainty in France and Germany, and households are bracing for a rise in unemployment. In many countries, inflation has already dipped below target. At its current level, the ECB’s key rate is viewed as restrictive by the vast majority of its Governing Council. There is every reason to lower rates further and adopt a more stimulative stance. Should that occur, it would mark a decoupling—a rare but not unprecedented divergence—between the ECB and the Fed.

In the United Kingdom, the term “stagflation” (stagnation combined with inflation) has frequently been used of late to describe economic conditions. GDP growth has been nearly flat for the past six months, yet signs point to accelerating wages and persistently high service prices. This represents one of the most challenging scenarios for a central bank, caught between the need to fight inflation and the desire to support the economy. The Bank of England has shifted back to an easing stance, though less markedly than the ECB.

In China, the economy remains weighed down by the purge of the real estate sector that began a few years ago. With domestic consumption weak, retail prices have remained nearly flat. Producer prices have been declining for approximately two years, thereby pressuring corporate profitability. To address this situation, the authorities have promised to provide additional support—most notably by easing monetary policy—but so far, actions have not lived up to the rhetoric.

In Japan, the economy is now experiencing re- inflation. Prices and wages are steadily recovering to the extent that monetary policy now appears excessively accommodative. For decades, the yen epitomized a low-cost funding currency. This marks a tectonic shift if the central bank continues—as it currently appears inclined to do—the upward adjustment of its policy rates.