Definition: What is growth investing?

Growth investing, in private equity terms, is the investment in growth companies of which here are a few definitions. Typically, growth companies display at least five of the following characteristics:

- Significant revenue andquick growth

- Run for growth objectives, not for profitability maximisation, quite often with the

consequence that the company is allowed to run at a loss. When already profitable, profit is typically re-investedin growth (acquisitions, hiring sprees, product expansion…)

- Often originally venture backed, these bootstrapped companies but are few and far between.

- Often still controlled by the founder, not necessarily led by the founder. Growth investors tend to take minority stakes.

- Typically already valued at well above 400 Mio USD or above, normally at a B, C or D round.

But it could be notably higher as growth companies are typically already unicorns (worth more than a billion dollars) or well on their way to becoming unicorns

- Typically with an exit foreseen in the next three to four years at a multiple on capital of about 3 to 4 times money

- No or extremely low leverage

- Less likely to fold than an early stage venture-backed company

Another way of defining growth companies would be to call them the emerging winners/survivors of an early stage venture capital portfolio, the companies which will return the fund and have the potential of becoming major companies in their own right. Growth investing therefore, is different from venture capital where one invests much earlier in the cycle, often 10 or more years away from exit with a high possibility of losing capital.

Growth investing vs growth buyout

To avoid any misunderstandings, there is also a sub-asset class called “growth buyout”.

Growth buyout companies tend to be fast-growing, but profitable companies. The difference being, indeed the profitability, the taking of majority stakes and the use of (usually quite limited) leverage. A growth buyout fund (like for instance a Vitruvian or a Verdane), will normally take majority stakes, apply no more than 4x ebitda leverage and run the companies for growth, not for profitability. This means lots of M&A, digitalisation, HR investments, R&D etc. but still with the aim to retain

profitability.

We hope this makes the difference between growth and growth buyout slightly clearer. As we can and do invest in growth buyout funds in our flagship fund of fund (Verdane, Insight Buyout Sleeve…), we do not need to offer them in a separate vehicle.

I tasked ChatGTP to do some IPO archaeology for me and it provided me with these gems:

Why aren’t growth companies run for profit?

I know most Belgian entrepreneurs prefer to run their companies at least break-even. So why don’t the growth entrepreneurs share this wisdom?

Basically, these growth companies are typically the emerging leaders in their respective niches, which are often emerging niches too. The expected wisdom in these circles is that the winner in its’

respective niche will eventually eat all the competition or will be able to set the price. The market is this big and potentially lucrative that it is worth the risk of running at a loss for the foreseeable

future.

Regular TTA investors won’t be shocked when I use a personal example to illustrate something basic but this happens to be a true example. When I worked at eBay some 20 years ago, a few of our

clients accused eBay of deliberately using “drug dealer” techniques.

Even I could never admit it, they had a bit of a point. Drug dealers setting up in town typically start selling their product below cost or even provide it for free, just to ensure that people are hooked. At the same time, they literally try to kill the competition for strategic neighbourhoods and supply chains. I can’t remember eBay being engaged in actual hit jobs. But yes, in certain markets, we did lower our prices just to get people hooked with the deliberate plan to hike the prices once we had the number one spot. We also overspent on marketing and advertising where needed, simply to

crowd out the competition. It’s business in domains where the winner takes it all.

When eBay couldn’t kill the competition, it simply would try to buy it. I’m not sure drug dealers have this option but M&A proved to be a killer tool for eBay (until the Skype acquisition, when things went a bit south, that is…).

That brave little AI which is ChatGTP provided me with this extensive list of eBay takeovers:

It is all about unit economics

Now while eBay was a profitable company (market places can be real cash machines, having no inventory at all), it was never really run for profit in the initial years. However, during my five-year spell at the company, I was able to appreciate that the company was run by metrics with unit

economics being a key one. Every country at eBay knew exactly what the customer acquisitions costs were for new clients, how many new clients turned into active clients and how much they brought in in fees and many more metrics to keep all the MBA’s in our staff widely entertained. As such, eBay

subdivisions were forgiven for not running at a profit if they could showcase they paid 20 USD to acquire customer that would generate 100 USD per year for the foreseeable future (5 years). You

could even forgive any fees for the first year if that helped to ramp up activity on the site. Yes, I know it’s quite similar to drug dealers handing out free samples outside schools, except this was legal.

The same can for instance, be said about Uber. Uber, or more specifically the C’s who backed Uber, basically subsidised taxi fares all over the world. As a result, they are now present in all major cities. Prices are now the same or even higher than a regular taxi but most people prefer to keep booking Ubers over the phone as it’s a more convenient (and safe) experience than hailing a taxi. Uber has just turned a profit, showcasing it does have unit economics.

This is where skill comes in. You have to be able to judge what screws and switches need and can be turned to turn to profitability. It’s typically a question of hiking prices and reducing overhead and redundant employees. Like eBay, who realised that maybe they did not need an office in every

European capital once they had successfully killed of all the competition or purchased them.

What spoiled the growth party?

There has been a real bubble in growth companies around 2020. Various factors were at play to cause this. During this period, we saw basically too much money chasing not enough deals. Seasoned VC’s with their own growth funds had follow-on rights so were less impacted by this. Specialised funds with a value-add like G-Squared or Alpha Capital could also pick and choose. But the

superpower of most funds was that they had money to deploy, too much money in hindsight. Softbank and Tiger Global are the main culprits here but we would also name others.

For instance, there is a well-documented story that Masayoshi Son, the CEO of Softbank, only met with Adam Neumann, the founder of WeWork, for just under four minutes before deciding that Softbank would invest an initial 4.4 billion USD into WeWork. The idea here was for WeWork to have so much money it could outspend all its competitors in signing up leases, decorating offices and

attracting customers to its co-working centres. The mistake here was that it’s very hard to cut costs as tenants and to increase rent prices. Basically, the monetisation part was not thought through.

Softbank had been hugely successful using this technique of providing emerging winners with massive amounts of cash which would allow them to win the race, hence justifying their dizzying valuations. This approach worked out spectacularly well with Alibaba for instance. It didn’t work

with WeWork, Oyo Rooms, Snapdeal or Zume Pizzas. Softbank does have balls of steel though. They are now forking out 1 billion USD to create the iPhone of Artificial Intelligence. It’s a wonderful world.

The other contributor to the bubble were the stock markets themselves. Historians will look back at the Covid years and scratch their heads. I shan’t get into the general political policies of this time, but I will share my thoughts on the stock market. Things went C-R-A-Z-Y in some areas, locking up people meant they couldn’t go to the casino anymore and, boy, did it show. Also, the US policy of just

sending anyone a cheque meant that suddenly everyone had cash. Given that a substantial portion of the population were either walking the dog or watching their screens, it did create a quite frothy stock market, especially in growth style stocks. Think the ARK ETF by Cathy Woods. Think the shares

of Zoom. Think the shares of any company benefiting from lockdown. The private equity and public equity markets are very closely aligned in the way that VC or even buyout aren’t really. VC’s and to a certain extent buyout firms smelled the money and cashed out as soon as they could. IPO’s went

through the roof. The public markets just gobbled it all up. It did not end well.

Getting back to the private markets, there are plenty of stories around of excess and greed. G-

Squared once bought secondary shares in Impossible Foods, the alternative hamburger meat company, just to sell it to a few hedge funds for triple the price just three months after the purchase. The hedge funds just wanted to show their clients some exposure to the alternative meat hype…. We think it is fair to say that in 2020 and 2021, some investors completely lost their discipline and just

threw money at the most shiny growth companies around.

The usual suspects in this game were names such as Softbank, Tiger Global, Coatue, D1 Capital, Lone Pine Capital, Maverick Capital and Franklin Templeton. Seasoned VC’s used to call this Hedge Fund Hotel. Entrepreneurs would call it easy money.

Top Tier Access also invested in growth in those years through G-Squared V and Northzone Growth II.

We still think they were good, solid choices. Northzone Growth II deployed rather slowly and kept out of the more insane deals. They were able to do this as they had follow-on rights on their most successful companies, meaning they did not have to bribe themselves in. Funds such as a Northzone also have the relationship with the founders where they can have a reasonable discussion about

valuations.

G-Squared also avoided the most hyped companies and negotiated some very stringent preferred rights to manage any downside risk at future rounds.

We politely declined Tiger Global on quite a few occasions. Something just didn’t feel right.

Will growth ever get back into favour?

The past 18 months have shown the longest “IPO winter” in history since the Great Financial Crisis. There are no more hedge funds, crossover funds or corporate venture funds in the market.

Down-rounds continue to significantly outpace the up-rounds in 2023 and quite a few more are in the books. Quite a lot of companies got a stay of execution by issuing convertible loans or other structured financing.

But then again, some companies, especially in the field of artificial intelligence, currently have no troubles at all attracting growth capital. G-Squared has quietly already bought some employee shares in OpenAI. Talk about a growth company here. They were the first company to get to 100 million

users just two months after product launch. Admittedly, it needed to raise more than 11 billion USD since it’s establishment in 2015. It’s rumoured to be worth about 80 or 90 billion USD on estimated revenues of about a billion USD this year. I from my side am happily paying my 20 USD a month to retain access to the latest version. I am also happily taking bets G-Squared will triple their amount invested.

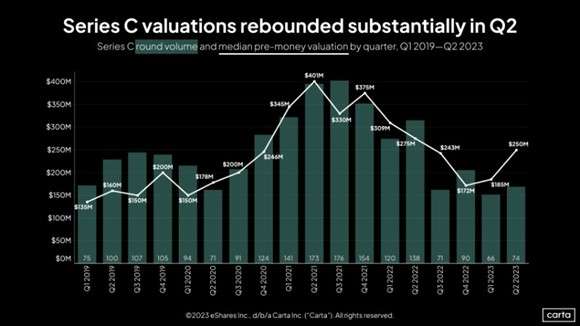

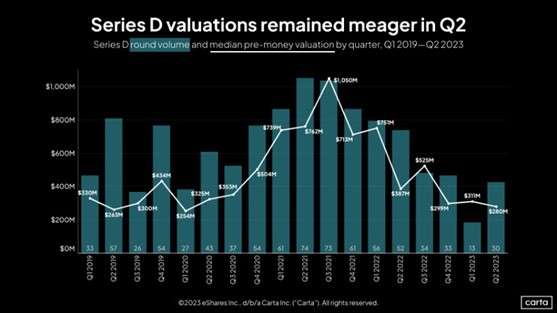

It is fair to stay however, that outside the field of AI, the valuations of growth companies are

nowhere near the manic levels they reached 18 months ago. Here are some interesting graph which I found on . They indicate a bit of a rebound for series B and C and a stabilisation of series D. I don’t have a crystal ball but this does look like a more rational market.

A brief overview of the IPO window and trade sales

There have been about 12 billion USD in 255 venture capital exits in the US in 2023 but the bulk here is to strategic buyers (read, tech giants such as Meta and the likes).

“Big tech” is currently not buying that many companies for the moment. There is growing attention from anti-trust regulators in the US and Europe which could help explain this. But traditionally, the likes of an Amazon, Apple, Google and Microsoft have been very active buyers of other tech companies.

Saying this, there seems to be a bit of a rebound in the tech M&A market in general.

As such, this is not bad, but the IPO window really needs to open in order for the growth investing motor to kick back into gear. Not only would re-opened IPO markets give a morale boost to growth investors, it would also set clearer indications in how to set valuations.

In our view, the IPO market is starting to hum again. The recent IPO’s of ARM, Instacart and Klaviyo went reasonably well. While the shares now trade slightly below their IPO offering price, all offering prices were at the upper range of the guidance provided. This indicated enough interest amongst

primary IPO buyers. Admittedly, the free floats of those three companies were rather modest. We also saw the Instacart’s IPO constituted a down round versus its latest private round. But the IPO’s happened and that’s the most important part.

The situation is of course evolving every day but in our discussions with the growth funds into which we have already invested, quite a few other IPO’s are being prepared as we speak. The CEO of Novo Holdings, the foundation controlling Novo Nordisk but also investing in other companies, is on record for stating the IPO market will open again . One senior investment banker at Jeffries states the IPO window could re-open from now.

The recent indication from the Fed that perhaps there could be at least one more hike before end of the year has dampened the mood on the stock markets to an extent. Then again, it is not unreasonable to think we are closer to the end of the interest rate hikes than we were to the

beginning.

A few swallows do not make a summer, as the proverb says, but perhaps winter could be over sooner than later? And perhaps it’s best to invest while it’s still winter?

We think the time is right to get back into growth. Valuations are a lot lower; conditions are a lot better. Every year, there is a steady supply of growth like companies. Picking the right manager is of course crucial here, the keyword being discipline. We off course have an idea.

Annex: A typology of companies:

| Sam’s fun list | Early stage startups | Growth companies | Buyout companies | Family businesses |

| Product | Doesn’t exist yet | Basic product exists, sell to as many as possible | Expanding new lines, streamlining existing lines… | What grandpa started |

| Personnel | PhD’s, students & entrepreneurs | MBA’s & executives | University degrees | People hired by grandpa |

| Revenue | None | At least 20 Mio | At least 20 Mio | Variable |

| Profitability | 10 years from now | Next year, but first we kill the competitor | Yes | Yes, for the last 50 years except for the War |

| Revenue growth | No revenue yet | At least 40% a year | At least 20% a year | Yes, as much as we can |

| Valuation metrics | We’d rather focus on paying out a dividend | |||

| Leverage | What’s that? | If we can | As much as we can | Grandpa hated the banks! |

| Way to address the boss | Bro! | John/Jean | Sir/Madam | Dad/Mom |