Europe at the polls: what’s at stake for the future ?

Bruno Cavalier, Chief Economist ODDO BHF Asset Management.

KEY HIGHLIGHTS:

- The last parliamentary term was marked by the pandemic and the war in Ukraine.

- The European economy has fallen behind its past trend and its rivals.

- The United States and China are implementing dynamic industrial policies that hamper free trade.

- In response, Europe must make further progress in integrating its markets.

- There is a pressing need for investment in Europe, and this calls for capital market union.

As it happens every five years, EU (European Union) citizens are called to elect the members of the European Parliament, on 6-9 June. The Parliament shares legislative powers with the EU Council (it votes on laws and the budget) and has powers of scrutiny over the Commission. At the first election of this kind, in 1979, the EU, which was then called the European Economic Community, consisted of just nine countries. This election was a democratic innovation with an average turnout of 62%.

Then, as the EU grew to 28 members, voter interest dwindled, reaching a low point in turnout of 43% in 2014. Europe had just suffered two recessions in the space of a few years, coupled with numerous financial and banking crises. The EU was no longer fulfilling its primary objective of working towards peace and prosperity. Euroscepticism was on the rise everywhere, and two years later, the British people voted for Brexit.

At the time of the previous election in June 2019, the economic and financial situation had improved. Far from being a model to emulate, Brexit had emerged as a factor of cohesion for the 27 remaining countries. In the eurozone, a subset of the EU, the survival of the single currency was no longer in doubt thanks to the actions of the ECB under the leadership of Mario Draghi. Renewed optimism was evident with voter turnout rebounding to 51%. In the months that followed, the new Commission chaired by Ursula von der Leyen set its sights high on carbon neutrality, digital transformation and the EU’s geopolitical influence.

Five years on, the European agenda has had to adapt to exceptional circumstances, to say the least. Two major and unforeseeable events occurred during the last legislature: the pandemic in March 2020 and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022.

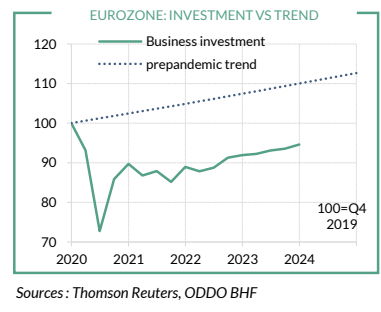

The pandemic led to a widespread lockdown, which in turn triggered the most severe recession in modern history. Admittedly, the rebound in activity was quick and massive once the health restrictions were lifted, but the European economy has yet to return to its pre-pandemic trajectory. As of early 2024, real GDP is 3.5% below what could have been projected by extending the trend in 2019. The level of investment spending is around 15 points below its trend (chart).

As for the war in Ukraine, it translated into a sectoral, macroeconomic and geopolitical shock of rare intensity. Several European countries, primarily Germany, depended on Russia for their supply of raw materials, especially gas. In the absence of immediate substitutes, energy prices soared in 2022, amplifying the inflationary pressures associated with pandemic- related disruptions.

As a result, Europe experienced the sharpest rise in inflation since the 1970s, leading to unprecedented monetary tightening. Inflation is now close to its target and the ECB will soon start to ease policy, but the shock to prices and credit conditions is still being felt. It is hardly surprising that a large proportion ofthe electorate is once again turning to Eurosceptic parties. Prosperity and security are not guaranteed.

Needless to say, the EU is not responsible for the global pandemic or the war in Ukraine. In fact, it has responded quite boldly to these shocks. In the summer of 2020, European leaders adopted a ‘recovery plan’ amounting to nearly 6 points of GDP over several years. The aim was to help the weakest countries through loans or subsidies to support demand across the EU and benefit all its members. While this approach is common at the national level, it was unprecedented at EU level.This plan, created outside the usual budgetary framework, was designed to be a one-off, with care taken to avoid debt mutualization. However, it could serve as a model if the EU decided to mobilise proportionate financial reduce to meet the challenges of increasing defence capabilities, investing in technology and pursuing the energy transition. Surely, these three objectives should garner support across the board. Who would not aspire to live in a safer, more innovative and less polluting world?

Meanwhile, the rest of the world has not remained passive in the face of these challenges. Both the US and China, despite their rivalry, are actively pursuing industrial policies that subsidise innovative sectors, from AI to electric vehicles. In contrast, the EU lacks a comparable scale of effort, partly because individual countries often prioritise national interests over the common good.

What can be done? There is no shortage of ideas on how to address the EU’s shortcomings. It is no secret that the single market is incomplete in the area of finance. In a report published in April, Enrico Letta, former President of the Italian Council, advocates advancing the union of capital markets to improve capital allocation and encourage investment. To help “Europeanise” companies and enable them to benefit from economies of scale, he also proposes creating a European business code that could constitute an optional alternative to the 27 existing ones, one in each country. In a few weeks’ time, Mario Draghi, former President of the ECB, is also expected to present his proposals for improving competitiveness. His initial thoughts emphasise the need to reduce fragmentation that hampers many sectors, from defence to telecommunications, research and supply chains.