The moment of truth for public debt

Bruno Cavalier, Chief Economist ODDO BHF Asset Management.

KEY HIGHLIGHTS:

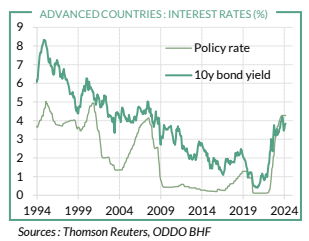

- The era of ultra-low interest rates is over and debt refinancing has once again become very expensive

- The average public debt of advanced economies now exceeds 110% of GDP

- This means fiscal policies must be rebalanced without delay to reduce deficits

- The longer such adjustments are deferred, the greater the risk of adverse market reaction

- There is a significant risk of debt slippage in the medium term in France, Italy, and the United States

Economic crises leave a legacy of high public debt. Expansion phases should be used as an opportunity by governments to reduce their debt and rebuild some headroom in their public finances. This is easier said than done. Let’s look at what happened after the last two major crises.

Following the global financial crisis of 2008-2009, the public debt ratio in advanced economies rose by 26 percentage points of GDP to nearly 100% on average. It never fell back in the following decade, with a few rare exceptions such as Germany. For years after the shock, economic growth remained sluggish. However, this did not jeopardise the sustainability of the debt, as interest rates were kept low by central banks.

In 2020, economies had to be shut down because of the pandemic. The resulting loss of income in the private sector was offset with public funds. The government debt ratio surged again by 19 points. Thankfully though, this time, the recovery was strong and swift, perhaps too swift since it triggered a surge in inflation. For the government, inflation is like a tax – said to be less painless than direct taxation – which makes it easier to accommodate increases in spending. However, it is not a long-term ‘solution’.

In total, the recovery has offset half of the increase in debt. The debt ratio was reduced from 123% at its peak in 2020 to 112% in 2023. This remains higher than after the global financial crisis. Moreover, to counteract the inflation shock, monetary policies were tightened, pushing up interest rates. The time has come to take stock.

What are the economic conditions for 2024 ?

Overall, the pace of growth has normalised. Inflation has come down from its peaks and, in Europe at least, is no longer very far from the 2% target. Monetary policy is likely to be less restrictive, yet a return to ultra-low interest rates is nowhere in sight. In summary, the factors determining public debt sustainability have changed compared to the pre-pandemic period.

Firstly, the fiscal situation of advanced economies has worsened as, after reacting to the pandemic, European governments also aimed to mitigate the 2022 energy crisis. Additionally, as we are an ageing society, the welfare state is becoming more expensive, and the potential for economic activity is diminishing. We also live in a world marked by geopolitical tensions that call for increased defence spending. According to IMF figures, the budget deficit of advanced economies has widened to a record 10% of GDP in 2020. In 2023, it still exceeded 5% on average, twice as high as before the pandemic.

Secondly, the planning of future budgets must take into account the rise in government borrowing rates, which are at levels not seen in more than a decade (graph). In the short term, the impact on debt servicing will be modest, since public debt has an average maturity of around seven years, but the cost will increase over time. With the rise in debt servicing, public resources will be diverted from productive use, which is harmful to future growth.

The main risk for debt management is that interest rates become higher than economic growth over the long term, as this could lead to a snowball effect. In such a scenario, tax revenues increase less quickly than interest charges on existing debt. This is far from being the case in European countries, but it is a risk worth considering.

If the interest rate and the growth rate were equal, the way to stabilise the debt ratio would be for governments to balance their budgets so that expenditure excluding interest charges is covered by taxes. While individuals habitually balance their budgets over time, it is less common for governments used to easy access to debt. For developed countries, such an effort would represent several points of GDP. The longer this adjustment is delayed, the larger and less credible it becomes.

Under these conditions, scrutiny by supervisory authorities, rating agencies, and financial markets will intensify. In 2022, the United Kingdom faced a mini-budget crisis because its fiscal policy was deemed too risky. Last year, France’s credit rating was downgraded, and recent revelations about the slippage of the deficit in 2023 have raised fears of an equivalent sanction in the near future. This year, the EU is reinstating its budgetary rules, and a dozen countries, including France and Italy, are set to undergo the excessive deficit procedure (EDP). In the United States, the director of the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), the bipartisan body responsible for medium-term fiscal projections, has declared the trajectory of federal debt as unprecedented. Yet, neither of the two presidential candidates seems to be concerned.

Governments can either maintain the status quo and risk facing harsh repercussions from the markets or establish a multi-year consolidation plan. The difficulty lies in finding the right balance so that this adjustment does not weigh too heavily on growth in the short term while remaining credible. In any event, we must be prepared to live with a very tight budget constraint.