Three questions about rate cuts: why, when, by how much ?

Bruno Cavalier, Chief Economist ODDO BHF Asset Management.

KEY HIGHLIGHTS:

- With the risk of inflation having largely receded, the rise in policy interest rates is now over.

- In 2024, central banks will pivot towards monetary easing.

- In a soft-landing scenario, the rate cut should be gradual.

- The markets are much more aggressive and could be disappointed.

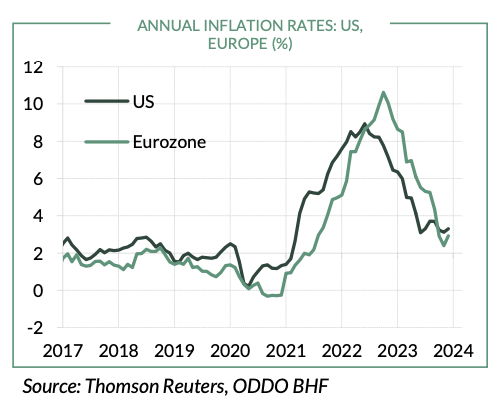

The inflation shock that was so prominent in 2022 has faded everywhere in 2023. In the United States, the inflation rate ended the year at 3.4% year-on- year, while in the eurozone it fell even further to 2.9%. We’ve come a long way from inflation peaks at 10%! Although inflation has not yet returned to the 2% target, it is no longer far off (chart). Against this backdrop, central banks have stopped raising their policy rates in recent months: since July for the Fed, since September for the ECB.

2024 is poised to be the year of monetary policy easing. The financial markets eagerly await this pivot, anticipating that it could occur as early as the first quarter and that it will be very pronounced. However, markets are not omniscient. Neither in 2022 nor even at the start of 2023 did they contemplate policy rates rising that high. That is why all angles of the problem need to be looked at in detail.

The first question is to understand why would the Fed or the ECB cut their policy rates. There have been many instances in the past where monetary policy was eased in response to a sudden shock. For example, to prevent the economy from sliding into recession or to mitigate its severity, or to prevent the markets from suffocating due to a lack of liquidity. The main objective of the central banks was to restore economic and monetary stability at all costs.

In 2024, the situation is different. This time, it is more about adjusting monetary policy in response to inflation converging towards its target. There are few cases in the past where this has happened. The only example that springs to mind is the situation in the United States in the mid-1990s. Faced with inflationary pressures, the Fed tightened its policy sharply in 1994, then began to reverse course in 1995. It was a complete success, with inflation easing without the economy falling into recession. In short, it was a textbook case of a soft landing, but one so rare that it was seen as an anomaly that would never happen again.

Are we currently experiencing a soft landing? There are many signs of it, particularly in the United States. In 2023, employment and income growth slowed without collapsing, unemployment remained low, household consumption and wealth increased, and inflation slowed down. In Europe, the situation is more at risk. Here too, the labour market has held up well, but consumption has stagnated, bank credit has dried up and the economy is flirting with a recession. If the Fed has reasons to ease its monetary policy, the ECB has even more incentive to do so. In any case, the monetary rules describing the “optimal” behaviour of central banks are starting to point towards easing in both regions.

The second question is to determine the best time to start a rate cut cycle. Here again, a brief look at history is useful. In the face of a shock, it is customary to react very quickly, sometimes even at emergency meetings, as witnessed during the financial crisis in 2008 or at the start of the pandemic in 2020. In these episodes, where inflation was not a threat, but unemployment risked skyrocketing, there was no reason to hesitate.

In the present case, a degree of caution is called for. There is no major shock justifying an aggressive reaction. The decision is therefore more difficult. On the one hand, the tightening implemented in 2022 and 2023 has not been fully passed on to the real economy. On the other hand, at a time when new disruptions in maritime transit are occurring, which will delay deliveries and may cause shortages, it is not necessarily advisable to support demand. Delaying the rate cut would allow for continued pressure on inflation… but at the risk of maintaining a restrictive policy for too long. Conversely, easing would breathe life into business and credit… but at the risk of boosting inflation. In our view, this risk seems non-existent in Europe but cannot be completely ruled out in the United States.

The final question concerns the extent of the rate cuts. It goes without saying that this question is inseparable from the previous two. In response to an economic shock or a financial crisis, it is advisable to cut rates very aggressively. As a reminder, the Fed cut rates by 475bp in 2001 (stock market crisis), 400bp in 2008 (financial crisis) and 150bp in Q1 2020 alone (pandemic). In contrast, during the soft landing of 1995, the cut was only 50bp.

In its projections from last December, the Fed has a median scenario where key rates are cut only three times in 2024. At the ECB, officials have so far refused to even discuss rate cuts. In both regions, the markets are more aggressive, expecting the equivalent of six or seven rate cuts. Is this consistent with a central scenario of resilient economic growth and only a moderate rise in unemployment? It is doubtful. If the general pattern of a soft landing materialises, there is no reason why monetary easing should be very significant.