Bruno Cavalier Chief Economist ODDO BHF AM.

Key highlights:

- This summer, economic trends diverged from region to region.

- In the US, consumer spending remains robust; however, it is waning in Europe and China.

- Europe is once again flirting with a recession; the property sector is particularly sluggish.

- While the surge in inflation has decelerated, it’s premature for central banks to declare victory.

- Nopolicy rate cut is expected for manymonths.

This summer, economic activity has displayed varied trends across different regions. Bolstered by consumer resilience, the US is on a trajectory towards a soft landing. Tensions in the labour market are gradually easing. The turbulence in the banking sector, which caused significant concerns last March, appears to have subsided. While the risk of a recession remains, it is now perceived as less imminent than it was a fewmonths prior.

In contrast, Europe’s household income remains under pressure. Business sentiment has plummeted over the past three months, a trend evident across all countries, most notably Germany. It also applies to all sectors, as services, which had previously shown resilience, are now losing steam. Over in China, following an upswing in activity after the easing of health restrictions, a sense of pessimism is emerging. The cautious spending from households and businesses reflects their lack of confidence in the Chinese government’s ability to support the economy, especially while cleaning out the residential construction sector. Overall, the risks to the global growth outlook are tilted to the downside.

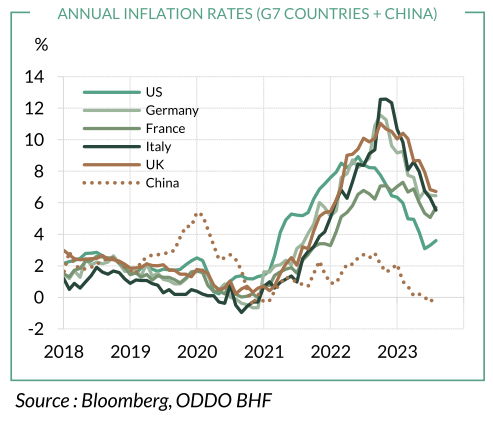

As for inflation, the shock appears to be subsiding, albeit at a slow pace and not without potential flare-ups. The surge in production costs, which peaked near 20% year-on-year in Spring 2022, has recently settled back to zero on a global scale. However, the recent uptick in crude oil prices in response to OPEC+ production cuts is a disruptive factor. Moreover, the waves of inflation and disinflation are misaligned. While goods prices have almost reverted to pre-pandemic levels, the same cannot be said of services prices and wages. On the whole, global inflation has receded from its peaked of nearly 10% last autumn to just shy of 6% this summer.

Despite undeniable progress in combating inflation, the inflation rate remains well above the 2% target in developed countries – China being the exception, as it teeters on the edge of deflation (see graph). Central bankers are therefore wary of claiming victory. Both the Fed and the ECB maintain a restrictive stance, in a bid to prevent investors from pricing in a premature monetary easing. Key interest rates will remain at high levels, and given the inherent delay in their ripple effect to the real economy, the restrictive effect on demand will intensify. The construction sector stands poised to bear the initial brunt of rising interest rates and the credit crunch. A slash in interest rates would only be conceivable if economic activity dips below potential trajectories, and crucially, if inflation moves very close to the target. This will take several moremonths, if not quarters. In our view, monetary easing is not likely beforemid-2024.

Inflation enacts a redistribution of resources among economic agents, creating winners and losers. With real income losses, consumers have been the main victims over the last two years. Wages have been slow to catch up with prices, and so far the process has been incomplete, especially in Europe.

Logically speaking, disinflation should swing in the opposite direction, restoring consumers’ purchasing power. Meanwhile, however, various determinants of consumption have evolved. Firstly, while labour market conditions remain robust, they are showing signs of weakening. Secondly, rising interest rates have driven up the cost of credit. Lastly, the government budgetary largesse seen during the pandemic and last year’s energy crisis has run out. While households may still tap into their “Covid savings”, this reserve is well depleted. In the United States, projections suggest this buffer might run dry by early 2024.

Unlike households, businesses have benefited from the inflation shock. Post-pandemic, various sectors grappled with excess demand and faced shortages of materials or workers. This situation favoured escalating selling prices beyond the hike in real production costs. Amid a disinflation phase, corporate profit margins will come under increased pressure, which in turn could lead them to scale back on hiring and investment expenditure.

Disinflation is also reshuffling the deck for governments. For two years, strong nominal growth fostered healthier public finance ratios. As a result, investors weren’t overly scrupulous about debt trajectories. The situation is now very different: the downward risks to economic activity combinedwith disinflation will weigh on tax revenues, while the rise in refinancing rates will increase debt servicing costs. In Europe, governments are planning their 2024 budgets under tighter constraints. The U.S. is gearing up for its 2024 electoral season. It’s hardly a good time for budget consolidation efforts but in return, this might prolong overheating and delay the decline in inflation.