Water is essential to life, but how to distribute it has become a thorny issue. We believe both public and private investment is essential.

Marc-Olivier Buffle, Head of Thematic Client Portfolio Managers and Research & David Lloyd Owen, Founder and Managing Director Pictet Asset Management.

The world needs nearly USD13 trillion in water and sewerage infrastructure investment over the next quarter century. That’s not something either the public or the private sector can do alone. But their joint effort has to be intelligently managed and based on long term thinking. Because experience shows that failure to do so leads to failed outcomes on both sides.

For universal access to water to be achieved by 2050 – which is to say, for all households to have access to safe sources of water, safe sanitation and for sewage treatment to be the urban norm – there needs to be USD8.8 trillion of infrastructure investment in developing countries and another USD4.1trillion in developed countries, according to estimates by David Lloyd-Owen, water industry expert and advisor to the Pictet Thematic Advisory Board.1

That amounts to some USD370 billion of investment every year. By contrast, current annual investment in water capex is running at just USD287 billion, excluding agriculture, according to analysis by Pictet Asset Management. Estimates for both vary throughout the industry – for instance, the OECD estimates needed investment at USD1 trillion per year – but most agree that there is a huge shortfall between what’s needed and what is being provided.

A way to go

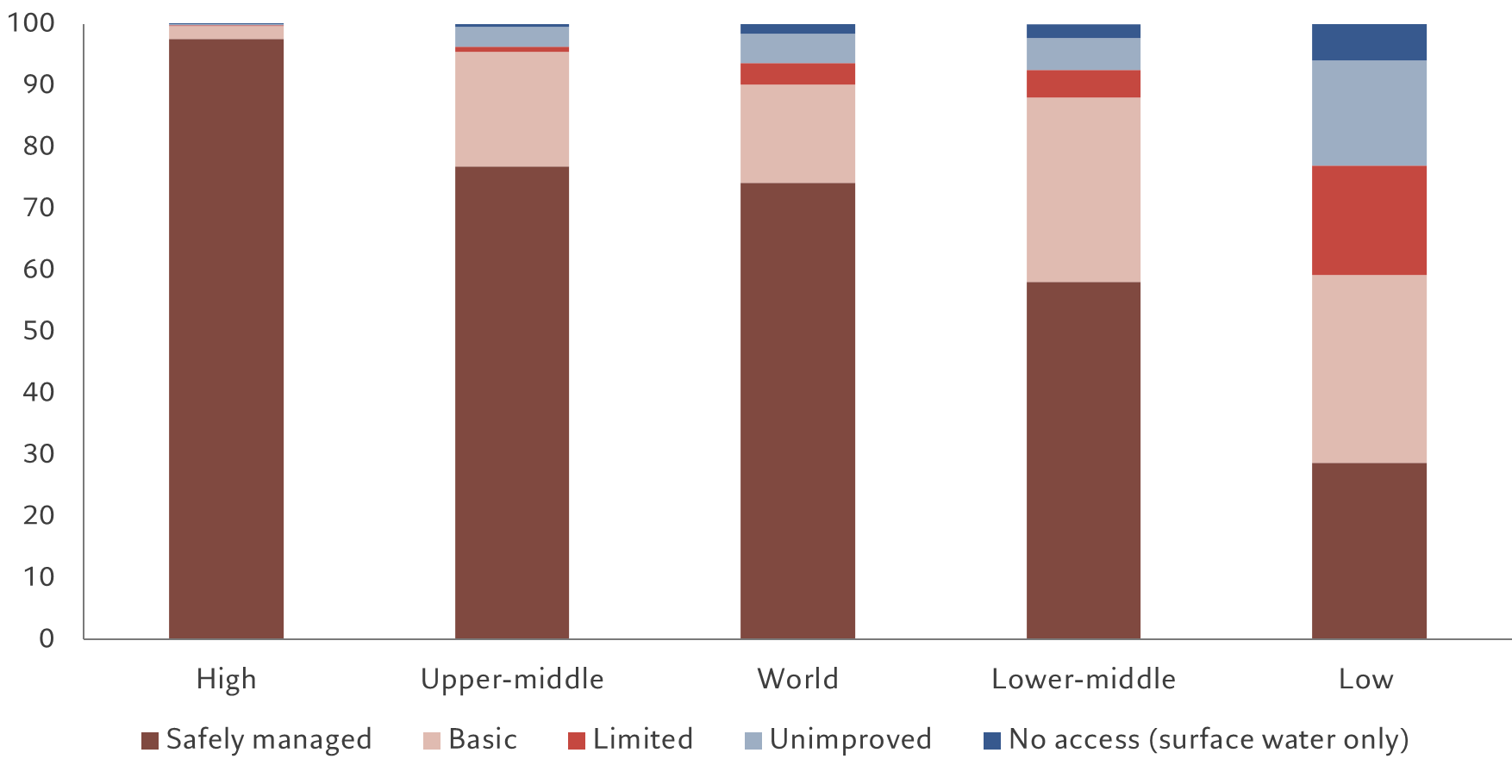

There is no question that the infrastructure is needed. Unsafe water is responsible for 1.2 million premature deaths each year, with some 6 per cent of deaths in low-income countries as a direct result of unsafe water sources.2 As of 2022, one in four people worldwide did not have access to safe water and 43 per cent lacked access to safe sanitation.3 Even among the high-income countries 6 per cent and 9 per cent lacked access to safe water and safe sanitation respectively. At current rates or progress, by 2030 23 per cent and 35 per cent will still lack access to safe water and safe sanitation respectively.

Figure 1 – Poor provision for the poor

Share of population with access to drinking water facilities, by country income, 2020

Source: Our World in Data. Data as at 24.07.2023.

A problem is that many of the water networks that developed countries rely on were laid down in the 19th century, during the first big push for public sanitation. For instance, London still uses the massive Joseph Bazalgette sewer system that was completed in 1875. As much of a miracle of engineering as it is, it can no longer sustain the metropolis’ needs. Which is why, in 2025, it is being supplemented by the Thames Tideway Tunnel, a 25 kilometre sewer that partly runs under the river, spanning one end of London to the other.

In a nutshell, investment is needed, whether public or private. Hence both capital expenditure and water bills are likely to rise globally.

Public or private?

While 20 per cent of the world’s population is served by private operators, the remaining 80 per cent is either served by state-run water companies or not at all. But the huge shortfalls in actual provision and quality suggest governments might not be the best providers of this essential public good.

For one thing, state-run providers need to have the right incentive structure and supervision, which isn’t always the case. In too many countries, such as in Indonesia and Kenya, provision is good among the wealthy, but inadequate for everyone else. Nor is failure limited to governments in developing countries. The Flint water crisis of 2014-17 in the US state of Michigan, where up to 12,000 children were exposed to high levels of lead in the water, was a failure on the part of the Detroit Water and Sewerage Department. There, an effort by the local authority to save what was ultimately a small amount of money incurred very large social and remediation costs.

Furthermore, governments create distortions with subsidies and other failures to price water adequately. That’s something bedevilling the US state of California, where water-intensive agriculture has blossomed in a semi-desert environment thanks to artificially cheap water, which, in turn, is largely down to the sector’s lobbying power.

Equally, there are private sector failures, such as in the UK recently, where England and Wales’s privatised water companies have come under considerable scrutiny amid stories of sewerage runoff onto rivers and public beaches.

Nuance needed

The UK offers a particularly interesting comparator for public and private provision of water services. Each of its nations – England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland – takes a different approach. The 10 Water and Sewage Companies in England and Wales were privatised in 1989. The nine English companies are a mix of public listed companies, held by private equity and subsidiaries of international companies. Welsh Water is a not-for-profit private company. They remain a government monopoly in Northern Ireland and Scotland. In general, the private companies have performed better, with lower leakage levels, more advanced sewage treatment and higher drinking water quality.

Their investment in infrastructure since privatisation is proportionately greater than it was during the 1970s and 1980s when the industry was state-held. Their services are also more efficiently run. For example, a household using 10 cubic meters of water a month would pay USD82.7 per month in Glasgow (Scottish Water) against USD39.4 in London (Thames Water) and USD53.3 in Cardiff (Welsh Water).4 Water is ‘free’ in Northern Ireland, meaning it is paid for through general taxation.

Some of the recent scandals about sewage in runoff is a function of Britain’s stricter monitoring than in other European countries, where for example beach water quality may not be measured for several days after heavy rainfall. What’s more, we estimate that UK water companies are responsible for less than 30 per cent of the river pollution, with agriculture and industry being the main sources of the problem.

Some failings, however, are to do with regulatory shortcomings. Generally speaking governments have become much better at negotiating and structuring public-private partnerships in utility provision. Whereas 30 years ago many contracts were poorly devised and ended acrimoniously, since then civil servants have built up plenty of precedents for how to frame agreements to ensure that their objectives are met at a lower cost than they’d be able to do as a state enterprise. But there are still places where regulators fall down – for instance unfamiliarity with how private equity companies operate, as in the case of Thames Water.

Doing it right

Well-regulated monopolies can produce excellent results, even in testing environments. In Manila and Phnom Penh, the private sector has provided universal and reliable water supplies with relatively little loss through leakage and theft – 11.6 per cent in Manila5 and 8.5 per cent in Phnom Penh6 compared to nearly 25 per cent in London.7

Many private sector participation contracts in the past two decades have focused on developing water and wastewater treatment assets and networks, with the municipalities concentrating on the customer-facing side of the service. This has seen dramatic reductions in the cost of developing new assets.8

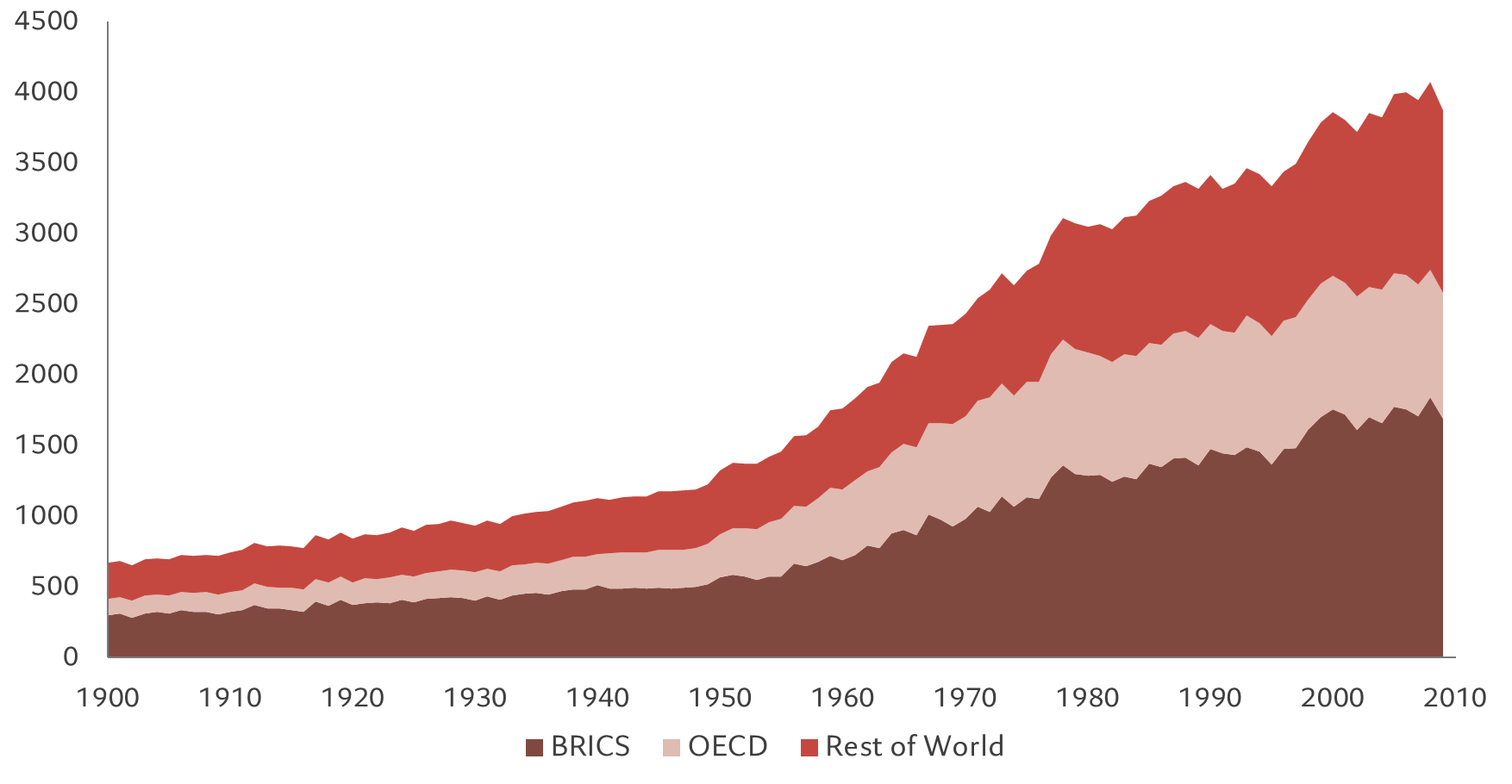

Figure 2 – A thirsty world

Freshwater use by aggregated region, billion cubic meters, 1901-2020

Source: Our World in Data. Data as at 24.07.2023

But overall, whether public or private, water and sewerage tariffs that cover costs are the preferred model because they’re sustainable – though subsidies can be targeted where affordability is an issue. Crucially, it’s important that investors continuously engage with water companies to improve pollution outcomes and fix incentive systems, and in turn, improve environmental and financial outcomes.

Clean water and safe sanitation are life’s true essentials. Their provision needs to be managed efficiently and for the maximum benefit. That often means involving private sector companies, albeit with appropriate regulatory oversight. This also needs the development of expertise and capacity to develop and deliver the necessary works. It means developing the most effective ways for the public and private sectors to work together for the greater good.9

[1] Lloyd Owen, D A (2020) Global Water Funding: Innovation and Efficiency as Enablers for Safe, Secure and Affordable Supplies

[2] Source: Our World in Data, ourworldindata.org/water-access

[3] Progress on household drinking water, sanitation and hygiene 2000–2022: special focus on gender. New York: United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) and World Health Organization (WHO), 2023.

[4] Global Water Intelligence tariff survey, 2022

[5] Manila Water, 2022 Integrated Report

[6] PPWSA, 2022 Annual Report

[7] www.thameswater.co.uk/about-us/performance/leakage-performance

[8] Kingdom, W., Lloyd Owen, D. A., Trémolet, S., Kayaga, S. & Ikeda, J. (2018) Better Use of Capital to Deliver Sustainable Water Supply and Sanitation Services Practical Examples and Suggested Next Steps, Water global Practice, World Bank Group, Washington DC, USA

[9] Lloyd Owen, D. A. (2022) The private sector and water services: a reflection, Water International, 47:7, 1032-1036